A comprehensive guide to emotional eating

This article was originally written by the Sequence clinic team (now known as WeightWatchers Clinic).

What is emotional eating?

Emotional eating, also called stress eating, involves eating in response to emotions and often occurs independent of physical hunger. For many, stress influences both the amount and types of foods they eat. Research shows that stress leads us to consume a greater proportion of our calories from highly-palatable foods that are rich in sugar, carbohydrates, and fats, even if our appetite (and thus our total daily calorie intake) is reduced due to stress.

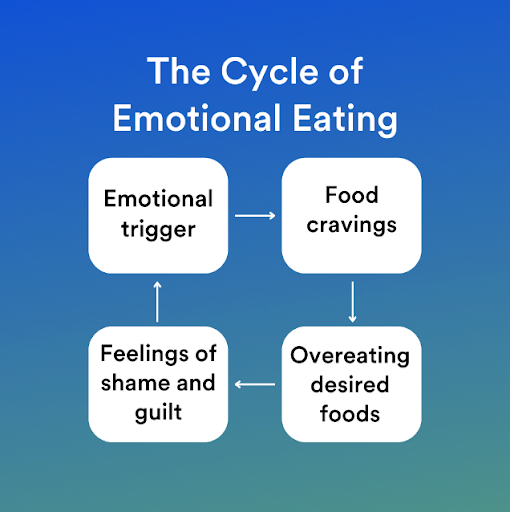

Eating in response to emotions can be problematic as many studies link emotional eating to weight gain, higher BMI, binge eating, and depression, not to mention the immediate wrongly placed feelings of guilt and shame that typically follow. While it’s often associated with negative feelings, emotional eating may happen in response to positive feelings too.

It’s important to note that emotional eating is not the same as binge eating disorder (BED). Although both involve overeating, BED is a diagnosable eating disorder that refers to eating abnormally large amounts of food in a short period of time while feeling a lack of control or compulsion to finish all of the food. In contrast, emotional eating involves eating in response to emotions and may include lower caloric consumption or irregular meal volumes compared to BED. Emotional eating is not associated with feeling a lack of control and may be part of an emotional disorder—such as depression, bulimia, or other mental illness—whereas BED is a disorder in and of itself.

Read on to learn about the science behind emotional eating and strategies for addressing it, all through a non-judgmental lens.

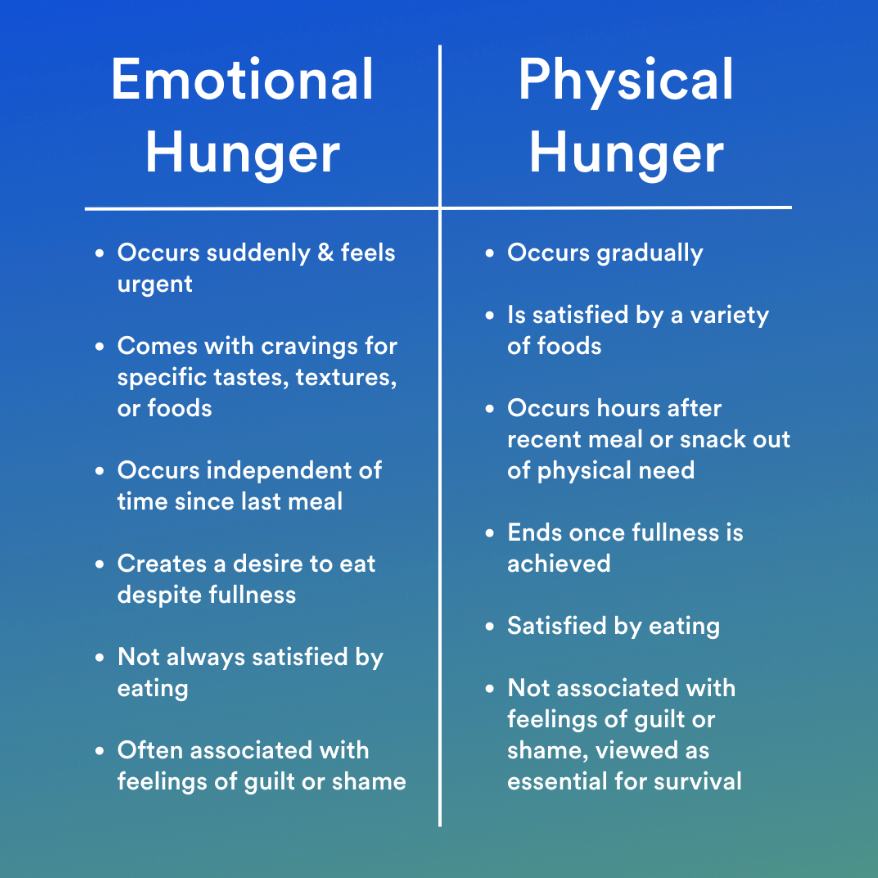

What’s the difference between physical and emotional hunger?

Physical hunger describes the body’s biological need for food and is marked by physical sensations like an empty stomach, inability to focus, low energy, and irritability. Physical hunger comes on gradually and is often tied to the time since one’s most recent meal and its composition. For example, a well-rounded meal that contains protein, healthy fats, fiber, and complex carbs will keep hunger at bay for longer than a meal that isn’t as balanced. Other factors like sleep and physical activity can impact our physical hunger too.

Emotional hunger often comes on suddenly and urgently—even in the absence of physical hunger—and typically includes a desire to eat something specific. Emotional hunger can feel hard to satisfy and often leads to eating until uncomfortably full.

See more examples of physical versus emotional hunger below:

Why are we driven to eat when we’re stressed or emotional?

On a biological level:

Immediately after a stressful event, we may experience appetite suppression thanks to the release of certain hormones that allow us to focus on the stressor at hand.

Hours and even days following the stressful event, a different category of hormones (called glucocorticoids) rise to stimulate our appetite and encourage us to eat. This biological response acts as a protective mechanism to help us get through a stressful and potentially life-threatening situation first, and replace our energy (through food) second.

If our stress goes unmanaged, levels of glucocorticoids remain elevated, leading to chronically stimulated eating behavior. Glucocorticoids can induce increased food intake and drive our preference for high-calorie foods. Since we made it through a stressful event, it makes sense that the brain would increase our desire to eat delicious, energy-dense foods to reward our survival skills since certain foods influence the activity of the brain’s reward centers.

It’s important to note that our stress response is individual. Various studies show that individuals who had higher levels of circulating cortisol following a stressor were more likely to consume more calories, particularly from high-fat foods. These findings help to explain why some individuals may struggle with emotional or stress eating more than others. (Read more about the effects of stress on total health in this blog post.)

On a behavioral level:

When we’re stressed, we’re quick to throw out habits that keep us even keel like exercising, cooking, maintaining social connections, and meal prepping. It’s likely that we spend time addressing our stressors instead of engaging in healthful practices (or our stressors leave us overwhelmed and unable to carry out our good habits when we need them the most). Leaving our stress unchecked may cause us to feel more stressed and lead us to seek convenience foods (like takeout or fast food) that lend to highly palatable, calorie-dense meals.

On a functional level:

Functional neuroimaging suggests that stress may deactivate our executive function in response to food cues. Executive function describes the set of mental skills that allow us to plan, focus attention, remember, think before acting, and juggle a number of tasks. The eight executive functions include self-control, emotional control, task initiation, working memory, self-monitoring, flexibility, organization, and planning and time management. If making decisions, following recipes, and eating slowly and consciously feels impossible during times of stress or heightened emotion, you’re not alone … you’re human!

Is emotional eating normal?

Before we continue, let’s normalize stress/emotional eating. You are unique, and so is your stress response. Experiencing a heightened desire to eat highly palatable “comfort foods” in an emotional state is not a testament to your lack of willpower or your ability to meet your health goals. In fact, it’s a biological survival response and a reminder that your body is incredibly smart.

Rather than shaming yourself for engaging in stress or emotional eating, first remind yourself that you are human. By tuning in, increasing awareness around your triggers, and learning about tools to manage your emotions, improving your stress/emotional eating tendencies is possible.

Beyond that, it’s important to recognize that food is not just fuel. The satisfaction you feel when eating your favorite foods, trying new cuisines, making a family-famous recipe, or celebrating with food isn’t just physical—it’s mental and emotional too. Eating to honor our emotions becomes problematic when it takes away from our quality of life and sidetracks us from reaching our health goals, rather than enriching our lives and becoming integrated into a sustainable approach to nutrition. Understanding this difference is crucial in establishing and maintaining a healthy relationship with food and taking back control of stress/emotional eating patterns.

What makes some individuals more prone to stress eating than others?

There are a number of physiological, physical, mental, environmental, behavioral, and social causes that may increase the likelihood of emotional eating.

Dieting:

Research shows that restrained eating—voluntarily restricting food intake as a means to control body weight—is a consistent predictor of overeating under stress. In one study, highly restrained eaters increased their intake of food—particularly those rich in saturated fat and sugar—under stressful situations, while “free eaters,” or those who didn’t regularly practice restraint, decreased their intake. One possible explanation is that people following a strict diet may develop feelings of intense deprivation which increases the likelihood that they’ll abandon their diet during stressful times. It’s important to note that stress eating occurs independent of dietary restraint, but high levels of restraint can worsen the effects of stress on the reward system, leading to more reward-based eating.

Feelings of deprivation in other areas of life:

Psychological deprivation doesn’t just come from food restriction. Not getting needs met in other life areas—like through adequate sleep, social connection, fun, self-care, or downtime—can create feelings of deprivation and lead individuals to seek fulfillment through food instead.

Poor body awareness and emotional regulation:

Dieting may also cause individuals to override their hunger and fullness cues. Over time, this may cause individuals to become out of touch with these bodily cues, leading to eating in response to emotions rather than physical sensations. Other factors like early childhood experiences, inability to identify and describe one’s feelings, and inability to regulate one’s emotions may contribute to poor body awareness (also called “interoceptive awareness”). Being unaware of our physical and mental sensations may prevent us from appropriately addressing our bodily state and promote emotional eating.

Depression:

Research shows that those who experience depressed mood show increased preference for and consumption of “comfort foods” and report the use of these foods as a means to alleviate adverse feelings.

Chronic stress, especially stress early in life:

Emotional eating has been associated with a reversed stress response in individuals who experienced chronic early life stress. In these cases, levels of the stress hormone cortisol are reduced rather than increased following a stressor. As a result, individuals are more likely to experience increased rather than decreased appetite after stress.

Fatigue:

Various studies show that poor sleep (~5 hours or less) and disruptions in circadian rhythm may increase our hedonic drive for food—in other words, our desire to eat foods for pleasure and reward rather than to satisfy biological hunger.

Poor gut health:

We may be more susceptible to stress eating if our gut health is off. Research shows that our gut bacteria play a role in the metabolism of dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in reward pathways, as well as serotonin, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine. As a result, our gut may indirectly influence our eating behavior through changes in our mood.

Food environment:

Emotional eating tends to take place with external eating. In other words, we’re more likely to overeat in response to food-related cues like the sight or smell of attractive food, whether we’re hungry or not.

Boredom:

When we’re bored our brains aren’t stimulated, which may lead to lower levels of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that’s strongly tied to feelings of reward and pleasure. Not only can eating provide distraction from our boredom, it can increase levels of dopamine, too.

Perfectionism and/or perfectionist thinking:

Perfectionism is a personality style characterized by striving for excellence and setting extremely high standards of performance. Research suggests “positive perfectionism,” a personality trait in which individuals have superior adaptive skills and change their goals or strategy if and when they fail to achieve high standards, has a positive health effect. “Negative perfectionism” describes individuals who set impractically high goals that often end in failure, leading to feelings of anxiety, depression, and decreased life satisfaction. Negative perfectionism may increase stress levels, and has been studied for its effects on emotional eating.

Does eating actually alleviate stress?

On a short term-basis, highly palatable foods can provide relief from negative emotions like stress and anxiety and improve mood states.

But repeated stimulation of the body’s reward pathways through food may lead to brain-body adaptations that can increase the compulsive nature of overeating and even suppress the activation of our stress pathways, leading eating to become a coping mechanism for many. Because of these adaptations, food may need to be more palatable in order to have the same stress-busting effects. Research also suggests that continued stress may not even be necessary in order to initiate the urge for highly palatable foods, meaning that stress eating can become a habit even in the absence of stress.

11 ways to address and prevent emotional eating

First ask yourself, “Am I actually emotionally eating?”

Eating large quantities of food is not the same as emotional eating. In one study, researchers suggested that some individuals mistook overeating with emotional eating when they reflected on their food intake from the prior evening. If you respond “no” to the following questions, then you may not be emotional eating: Did my hunger feel urgent? Was I tired, lonely, bored, or anxious? Did I crave a specific food, taste or texture?

Interview your hunger:

Before eating, practice the “HALT” technique to check in with yourself about your hunger. Are you hungry, angry, lonely, or tired? This method is based around the idea that we’re more likely to make poor decisions in any of these states.

Eat regularly throughout the day:

Not eating adequately during stressful times may worsen cravings for highly palatable foods since our bodies may seek fast-acting nourishment if we’re not getting enough from protein, healthy fats, fiber, and complex carbohydrates. Plus, undereating may only fuel emotional eating by leading us to feel like we have no control over food if we’re experiencing both biological and emotional hunger at the same time. Unsure of how to build a balanced meal? Our balanced plate framework is the perfect place to start. And if you struggle with finding time to eat during stressful times, simple actions like setting an alarm on your phone to eat or scheduling your lunch break into your calendar can help to promote regular meal times.

Practice mindful eating:

Keyword: Practice. The skill of mindful eating is like a muscle; the more we use it, the stronger it gets. Mindful eating is a practice that engages all of our senses to experience and enjoy our food choices. Eating more slowly, chewing thoroughly, acknowledging where your food came from, and noticing the color, smell, taste, and textures of food are all examples of mindful eating.

Understand your triggers through journaling:

Triggers for emotional eating will vary from person to person, but journaling about your emotional eating experience can help identify trends. Journaling aids in processing emotions, creates pause, and provides clarity, so while it may help with your emotional eating journey, you may find that it lowers overall stress levels too. Some useful journal prompts include: What was happening before my bout of emotional eating? What emotions trigger me to emotionally eat? How else can I cope with these emotions? Have I eaten enough food today? Have I eaten regularly today? What would be helpful for me instead of eating?

Ditch the diet mentality and avoid restriction:

Even when you’re eating enough food, labeling certain foods as “off limits” can create psychological deprivation, leading you to eventually eat that food and become overly full. It’s easy to label this as emotional eating instead of recognizing that the restriction around that food caused the over eating.

Build your personal emotional regulation toolkit:

Emotional regulation includes efforts to up- or down-regulate both positive and negative emotions that take place under stressful and non-stressful occasions. Building a list of strategies to deal with emotions like stress, loneliness, sadness, boredom, or anxiety, can offer solutions when your mental state is compromised or your brainstorming power is limited. For example, I know that listening to my favorite Spotify playlist and organizing my space helps ease my stress and switching up my scenery and calling a friend helps to address feelings of loneliness.

Nourish yourself in other areas:

Emotional eating may be the result of unmet needs. Improving your sleep, engaging in regular exercise, eating balanced meals, staying connected to loved ones, relaxing, flexing your creative skills, and feeling fulfilled are essential to preventing feelings of deprivation.

Give yourself some grace:

Getting upset after a bout of emotional eating only extends the emotional experience. Do your best to reflect back on the events that led to your experience, identify areas that may need more attention, and move forward with a growth mindset. Roadblocks are part of the process, but viewing them as learning opportunities instead of obstacles may help you to feel “unstuck.”

Create structure:

Managing our emotions is easier when we have habits and structure that we can fall back on despite our feelings. Sticking to a consistent bedtime schedule, eating at regular times throughout the day, and treating workouts like appointments with yourself may sound dull, but sparing mental energy and decision-making power is key during stressful and emotional times. Habits are like mental shortcuts that help to automate our behavior, so while building health habits may feel effortful at first, they may actually save us effort in the long-run.

Set realistic goals:

“Aim for progress not for perfection” sounds like a cliché, but setting high standards around perfecting your emotional eating may lead to failure and add fire to the emotional experience. I personally love SMART goals, which are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. For example, “I will set a timer on my phone for two minutes and breathe deeply the next time I am overwhelmed with emotions” feels more specific and achievable than “I will stop emotionally eating.”

Closing thoughts:

The emotional eating cycle can be vicious, but a little awareness can go a long way. Occasionally using food to lift your spirits or even amplify positive emotions is a perfectly normal part of life, but leaning heavily on food for comfort may be counterproductive to your health goals.

Related Articles:

- Ways To Cope With Stress

- Weight Health: The Key to a Balanced Lifestyle

- How Your Gut Health Affects Your Weight