The Most Important Things to Know About Diabetes Types

What are the types of diabetes?

Broadly speaking, diabetes is a condition in which the body is unable to regulate glucose (a.k.a. blood sugar), causing a surplus of it in your bloodstream. If left untreated, that surplus can affect your body in a number of ways, leading to complications like heart disease and impaired vision. But root causes and treatments differ among the four distinct types:

- Type 1 Diabetes

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Prediabetes

- Gestational Diabetes

What is type 1 diabetes?

Accounting for about 5 to 10% of diabetes cases, type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disorder. It’s sometimes referred to as juvenile diabetes, since most people with the condition get diagnosed in their youth, but adults can develop T1D too. It happens when antibodies attack cells in the pancreas that release insulin, a hormone that helps translate blood sugar into energy.

“We need insulin in our body to control blood sugars,” says Dr. Amy Warriner, M.D., a professor in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and director of the UAB Weight Loss Medicine programme. Without enough of it, blood sugar levels rise.

Risk factors

Anyone can develop T1D, but researchers still aren’t sure why it happens. What they do know is that genetics play a big role. Those with no family history of the disease have a 0.4% risk of developing it, while having a parent with the condition raises that to 5%. Interestingly, says Dr. Warriner, your father’s history may matter more here. “What we’ve found with the research is that it’s more likely to be genetically inherited from paternal lines than maternal lines.” The American Diabetes Association puts it at a 1 in 17 chance of winding up with T1D if your dad has the condition, versus 1 in 25 or 1 in 100 if your mother does, depending on her age at your birth. Other potential factors include exposure to certain viruses and environment. (It’s more common in cold climates.)

Symptoms

T1D often develops faster than the other types of diabetes, but symptoms may not show up, especially early on. If they do, they can include things like frequent bathroom trips, feeling thirsty, and weight loss. Since the condition often impacts children, parents and caregivers may be the ones who notice the signs, such as an uptick in accidents in kids who are potty-trained, says the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Treatments

“As soon as someone is diagnosed with T1D, they get started on insulin. No ifs, ands, or buts,” says Dr. Warriner. This is the case even when insulin production hasn’t stopped completely—a phenomenon known as honeymooning, used to describe a period of time when a person with T1D is still making some insulin, she says. The insulin can be administered through daily shots and, eventually, an insulin pump.

Though not necessarily a treatment, glucose monitoring is also prescribed as a way to check and help maintain normal blood sugar levels—done through a wearable device called a continuous glucose monitor, or with a meter that requires you to poke your finger and put a drop of blood on a test strip.

While type 1 diabetes can be well managed, it’s a lifelong condition that can never be cured or go into remission.

What's the difference between type 1 and type 2?

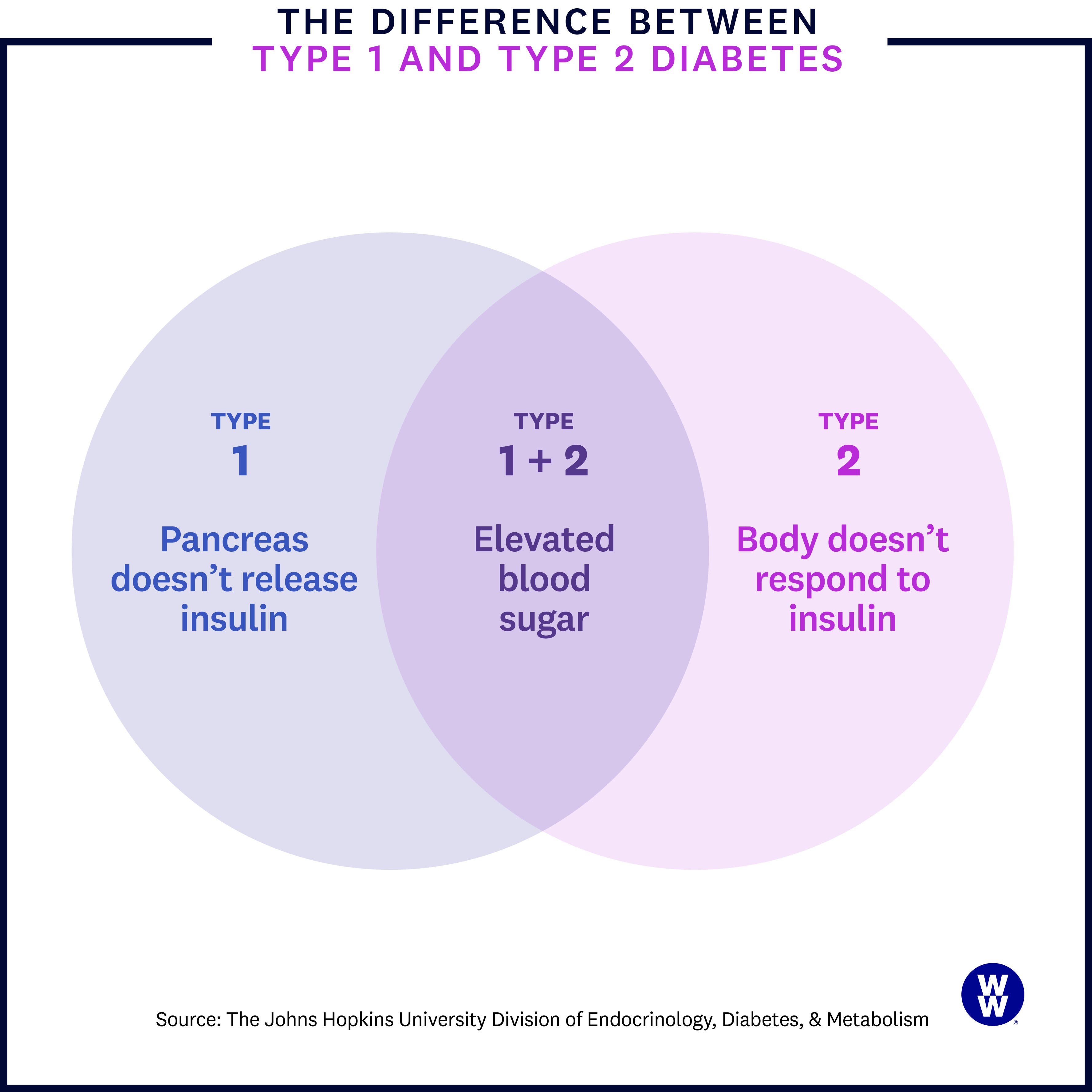

It’s all about the insulin. As we mentioned earlier, your pancreas releases insulin, which brings glucose (blood sugar) to your cells for energy. In T1D, the pancreas no longer provides adequate amounts of insulin to keep blood sugar levels in check. But that’s not the case with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

What is type 2 diabetes?

In T2D, your pancreas still releases insulin, but your body just doesn’t respond to it the way it should—this is called insulin resistance. When that happens, over time, blood sugar levels rise.

“Type 2 diabetes is typically thought to be a gradual onset of insulin resistance,” explains Dr. Warriner. Gradual is an important keyword here because people with T2D often don’t notice symptoms of the condition right away, or ever.

Risk factors

Like with type 1 diabetes, genetics are a major player. Research reveals that if both of your parents had or have T2D, you have a 70% chance of developing it yourself—and even just one parent with the condition puts you at a 40% higher risk. Other factors that increase your risk: a history of gestational diabetes or prediabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), having a BMI over 30, long-term use of steroid medications, and coming from marginalized racial and ethnic communities. (The latter is largely due to complex disparities in social determinants of health, such as decreased access to medical care.)

Symptoms

Since T2D can start slow, you may not notice symptoms. “For example, if you get diagnosed with type 2 diabetes with an A1C of 7%, you’re not going to have symptoms necessarily,” says Disha Narang, M.D., an endocrinologist and the director of obesity medicine at Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest Hospital in Lake Forest, Illinois. (A1C is a common diabetes test that gauges your average blood sugar over a three-month period—higher than 6.5% indicates T2D.)

Over time, however, you may experience hallmark symptoms, like having to pee more often, being super thirsty, or feeling very tired. And you may also experience some unusual signs—symptoms you might not immediately connect to diabetes. These include acanthosis nigricans, a darkening of the skin (commonly on the back of the neck), recurrent yeast infections, or urinary tract infections.

Treatments

Unlike with T1D, people with T2D have a variety of treatment options to choose from. Alongside standard glucose monitoring, the most popular treatments are oral medication, insulin therapy, and lifestyle changes.

Oral medications, like metformin, are often prescribed to help the body use insulin, ramp up insulin production, or decrease insulin resistance. If blood sugar is still above where it should be, then insulin is sometimes prescribed, says Dr. Narang. A critical piece of any treatment plan, however, is lifestyle—encompassing a nutrient-rich diet, increased exercise, and, in many cases, weight loss.

Research shows that modest weight loss, just 5 to 7%, is enough to improve blood sugar levels in people who are overweight or obese with T2D. Higher weight loss can even put type 2 diabetes into remission—a.k.a. when A1C levels are below 6.5% for at least three months with no glucose-lowering medication. Ultimately, what's important is that you find a plan you can stick with, not a quick fix, says Dr. Narang. “What’s most conducive toward appropriate chronic health or weight management is the [plan] that you can sustain the longest.”

That’s why livability is core to the WeightWatchers® programme—and that includes our Diabetes-Tailored Plan. No foods are off limits, but the plan guides you toward meals that are less likely to rock your blood sugar. In a six-month multicenter trial, members lost an average of 5.7% of their weight, and reduced hbA1c levels by an impressive .76%.*

What’s prediabetes?

Sometimes referred to as borderline diabetes, prediabetes is when your blood sugar levels are elevated, but they haven’t passed the threshold for type 2 diabetes. According to the American Diabetes Association, prediabetes is diagnosed in one or more of the following ways:

- A1C level between 5.7% and 6.4%.

- Fasting plasma glucose between 100 and 125 mg/dl

- Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 140 and 199 mg/dl.

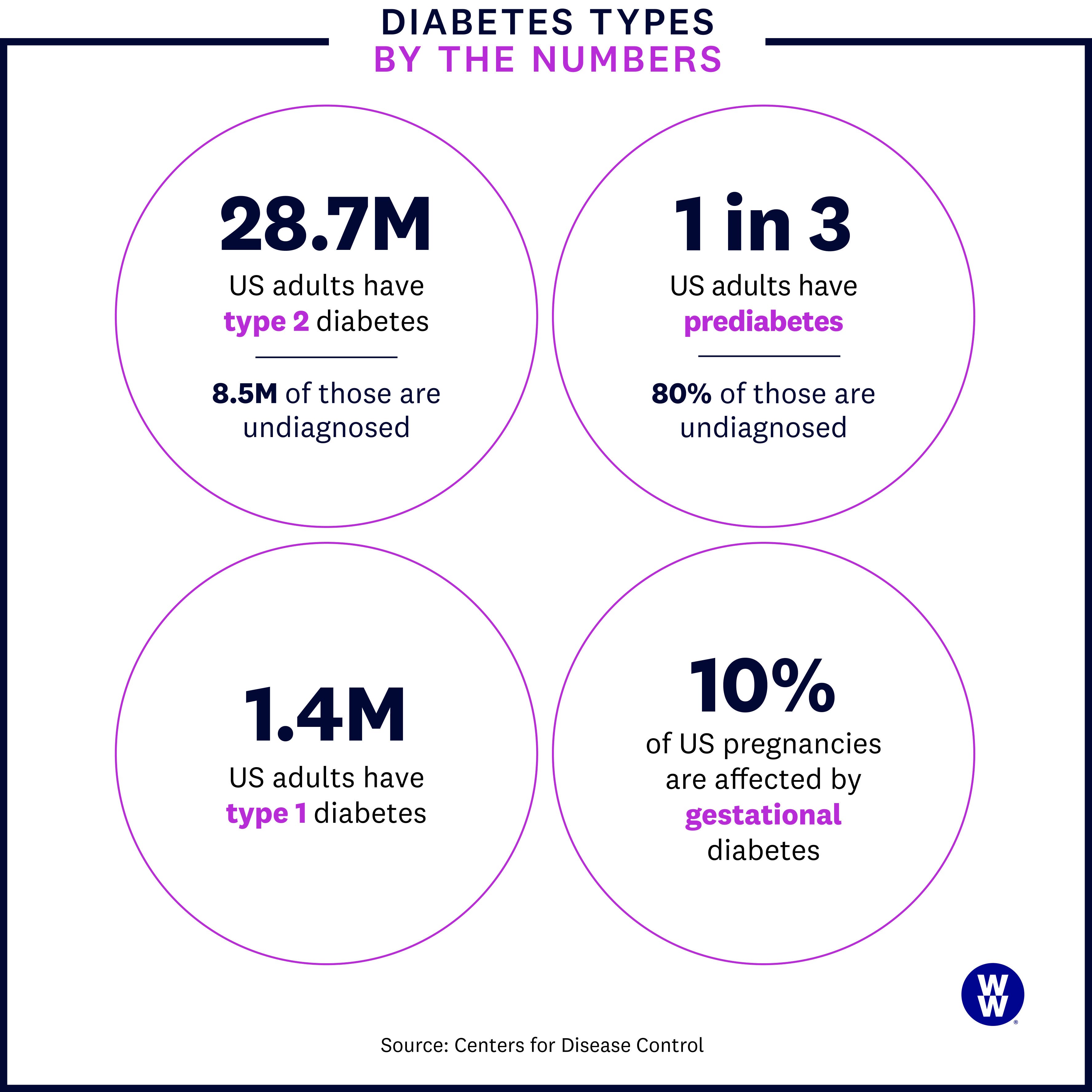

This type of diabetes is incredibly widespread: The CDC estimates that more than 1 in every 3 adults in the U.S. have prediabetes, with 80% completely unaware that they do. Prediabetes isn’t limited to adults: Nearly 1 in 5 preteens and teens between 12 and 18 years old also have the condition, according to a 2019 CDC study published in JAMA.

Risk factors

Since type 2 diabetes is, in many ways, a progression of prediabetes, many of the risk factors are the same, including: family history, BMI over 30, or conditions such as Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), or high blood pressure.

Symptoms

You may have prediabetes and not notice anything amiss, since it’s the earliest stages of the condition. “Symptoms like frequent urination and increased thirst typically present in much more severe cases of diabetes,” says Dr. Narang.

So then how are you supposed to catch it early? Stick with your annual physical. Once you hit 45, your doctor should start screening you for prediabetes every three years. If you have excess weight or have obesity, new guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advise you to start testing at age 35.

Treatments

Early action can make a major difference. “You have a better chance of putting prediabetes into remission than putting type 2 diabetes into remission,” says Dr. Warriner. “So if you’re able to make lifestyle changes before you’re diagnosed with diabetes, that’s optimal.” These changes echo those for T2D and include getting more exercise, a nutrient-rich diet, and reducing processed foods and portion sizes as a way to lose weight if needed.

When does prediabetes turn into type 2?

Prediabetes may develop into type 2 diabetes once your A1C levels surpass the prediabetes range, 6.5% and up. But know that prediabetes isn’t a set-in-stone path toward T2D. Frame your diagnosis as a nudge, says Barbara Sassower, a registered dietitian nutritionist, certified diabetes education specialist, and WW certified diabetes educator. “I often explain it to clients like, would you wait around to see flames before calling the fire department, or would you get help when you see the smoke?”

Tell Me More About…Treating Prediabetes

Q: Does losing weight really help prevent prediabetes from turning into T2D?

A: It does! In oft-cited research, people at high risk of developing T2D took part in the lifestyle initiative portion of NIDDK’s Diabetes Prevention Programme for three years and were able to reduce their risk by close to 60%. With the help of support groups, changes included dropping 7% of their body weight and working out regularly. Even better? Their risk was still lower 15 years later.

Q: Can medication help too?

A: Medication may help. In that same study, those who took metformin twice a day, which is commonly given to patients with T2D, reduced their diabetes risk by 31%.

Q: So can I just take meds?

A: Not exactly. Narang cautions that meds alone aren’t the answer, explaining that, “if [someone hasn’t] changed the way that they eat or the way that they move, then no amount of medication is going to change the inevitable in terms of developing diabetes.”

What is gestational diabetes?

While other types of diabetes can pretty much impact anyone, gestational diabetes occurs exclusively during pregnancy. The uptick in hormones—along with factors like having excess weight pre-pregnancy—can create insulin resistance and lead to a rise in blood sugar levels.

While gestational diabetes occurs in just up to 10% of pregnancies nationwide, recent research suggests that number is going up. A 2021 study in JAMA found that the rate of gestational diabetes rose around 30% between 2011 and 2019. Researchers pointed to factors like obesity and low exercise rates to help to explain the increase, though they’re studying this further to learn more.

Risk factors

Obviously, the biggest risk factor here is pregnancy. But the risk increases if you've had gestational diabetes in the past, have a family history of T2D, have a BMI over 30, previously gave birth to a baby over nine pounds, and have other related conditions, such as high blood pressure, PCOS, or prediabetes. It’s also more pronounced in certain racial or ethnic groups. The same communities at higher risk for T2D—including African Americans, Hispanic or Latino, American Indians, and Alaska Natives—are also at higher risk for gestational diabetes.

Symptoms

Gestational diabetes usually occurs without symptoms, but it’s standard practice to test for it in the second trimester or early in the third trimester, usually between 24 and 28 weeks, as per The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines.

Treatments

Healthcare providers take gestational diabetes very seriously because of its potential impact on both baby and the person who is pregnant. For the baby, risks include premature birth or low blood sugar levels, both of which may require time in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). For the one who is pregnant, gestational diabetes can increase your chance of developing preeclampsia, a dangerous condition marked by high blood pressure.

For this reason, women with gestational diabetes are closely monitored, both by their provider and using devices like a glucose monitor, to make sure blood sugar levels are under control. Lifestyle changes like diet modifications are key, and your OB or midwife may recommend a dietitian or nutritionist to help you implement these.

If high blood sugar levels persist, Dr. Narang says providers are quick to turn to other therapies—most commonly insulin, since it won’t impact the baby. “It’s imperative to make sure that we are maintaining tight blood sugar control in our pregnant population,” she says.

Once the baby is born, gestational diabetes goes away on its own. To make sure everything looks good, you’ll likely have your blood sugar levels tested between one and three months postpartum.

Can you have more than one type of diabetes?

According to a review published in Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism, the term double diabetes has been used to refer to people with type 1 diabetes who have overweight or a family history of type 2 diabetes, and who develop insulin resistance—a key feature of type 2 diabetes, not type 1 diabetes.

That doesn’t warrant a double diagnosis, though, says Sassower. “There may be features of type 2 diabetes that present with type 1 diabetes," she says. Even with T1D, where insulin resistance isn’t part of the underlying condition, factors such as carrying excess weight can lead to it.

Bottom line—your condition may manifest in a variety of ways, but you’ll only technically have one type.

*Based on a 6-month multicenter trial. Apolzan JW, et al. A Scalable, Virtual Weight Management Programme Tailored for Adults (n=136) with Type 2 Diabetes: Effects on Glycemic Control. Presented at American Diabetes Association’s 82nd Scientific Sessions. 2022.