The most important things to know about the causes of diabetes

What's included in this article:

What causes type 1 diabetes?

Sometimes referred to as juvenile diabetes, type 1 diabetes (T1D) was thought to surface only in childhood. Researchers now know it can develop in people of all ages. An analysis published in The Lancet (which was limited to individuals of white European descent in the UK) found that 42% of those living with T1D were diagnosed after age 30.

A lifelong autoimmune disease, T1D strikes when the body’s immune system basically does a 180 on itself, attacking and destroying cells in the pancreas that produce insulin, a hormone needed to lower the amount of sugar in your bloodstream. As a result, the body ends up with too little insulin and too much blood sugar.

“Because the immune system destroys these insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, the pancreas can’t produce insulin, which means that patients become dependent on insulin therapy to remain healthy,” says Dr. Tom Donner, M.D., an Associate Professor of Medicine and the Director of the Johns Hopkins Diabetes Center, in Baltimore, United States.

Type 1 diabetes is largely believed to be the result of genetics and environmental factors that aren’t yet understood. We know people can be genetically predisposed to T1D, but we’re not sure why the disease is triggered in some people with the predisposition and not others, says Dr. Jane Reusch, M.D., a Professor of Medicine, Bioengineering, and Biochemistry and the Associate Director of the Ludeman Family Center for Women’s Health Research at the University of Colorado, United States. That’s what leads many experts to suspect that environmental factors play a part.

What raises your risk of type 1 diabetes?

Scientists believe family history (i.e., you have a parent or sibling who has the disease) is the biggest risk factor. According to the American Diabetes Association, if both parents have T1D, a child’s risk is between 1 in 10 and 1 in 4.

Increasingly, researchers are learning about other potential contributing risk factors for type 1 diabetes, including higher maternal age at birth (defined as over 35), childhood obesity, higher-sugar diets, and viral infections either in utero or very early on in childhood.

Geography is also thought to play a role. It’s unclear why, but studies show those living at higher latitudes are more likely to have T1D; Finland consistently reports the highest incidence rate of T1D in the world.

Although T1D can appear at any age, in childhood, it tends to peak at two distinct times: between ages 4 and 7 and between ages 10 and 14.

What causes type 2 diabetes?

Unlike T1D, people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) do make some insulin, but their bodies can’t use it properly. People with T2D also tend to be insulin-resistant, meaning the body prevents insulin from doing its job of moving glucose from the bloodstream and into cells, providing them with the energy to fuel the body. Because glucose gets stuck in your blood, it causes high blood sugar. This is all coupled with a decreased ability to produce insulin overall.

The most common form of diabetes, T2D affects up to 95% of those with diabetes. T2D is caused by a combination of genetics and lifestyle factors, including having excess weight or obesity and a lack of physical activity. Studies show there is a clear link between T2D and obesity, as obesity can cause insulin resistance.

How do weight, diet, and exercise impact your risk of type 2 diabetes?

If there’s one thing researchers know about the environmental factors that can contribute to developing T2D, having excess weight, a poor diet, and not moving enough are the main offenders. “Following a healthy eating plan, losing excess weight, and getting in regular physical activity can help improve insulin sensitivity and blood sugar control,” says Barbra Sassower, RDN, a registered dietitian and certified diabetes educator at WeightWatchers®. And the good news is these are all things you can control. Here’s a closer look at how these factors play a part:

- Weight

Excess weight—i.e., a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or above—increases the likelihood of developing T2D. Here’s why: When you’re carrying extra weight, glucose can’t get into cells as easily, which causes insulin resistance, a proven risk factor for T2D.

Where you carry the weight matters too. Extra body fat, particularly in your belly, can contribute to insulin resistance. Known as visceral fat, this is the type of fat you can’t see because it surrounds internal organs and causes inflammation throughout your body.

- Diet

A diet that’s high in sugar and saturated fat can lead to excess weight, which can then lead to type 2 diabetes. But these saboteurs can also directly drive up your risk of T2D by negatively impacting insulin, Sassower says. Diabetes Australia recommends that people with T2D follow the Australian Dietary Guidelines Healthy Eating for Adults and Healthy Eating for Children. These guidelines recommend that a wide variety of nutritious foods be enjoyed from the below five food groups every day:

- Plenty of vegetables of different types and colours, and legumes/beans

- Fruit

- Grain (cereal) foods, mostly wholegrain and/or high cereal fibre varieties, such as breads, cereals, rice, pasta, noodles, polenta, couscous, oats, quinoa and barley

- Lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds, and legumes/beans

- Milk, yoghurt, cheese and/or their alternatives, mostly reduced fat

And drink plenty of water.

In addition, the Australian Dietary Guidelines suggests limiting intake of the following nutrients and foods:

- Limit intake of foods high in saturated fat such as many biscuits, cakes, pastries, pies, processed meats, commercial burgers, pizza, fried foods, potato chips, crisps and other savoury snacks.

- Limit intake of foods and drinks containing added salt.

- Limit intake of foods and drinks containing added sugars such as confectionery, sugar-sweetened soft drinks and cordials, fruit drinks, vitamin waters, energy and sports drinks.

- Limit intake of alcohol if you choose to drink.

- Exercise

Physical activity is important for people living with diabetes. The American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention note that being active makes your body more sensitive to insulin, which helps manage your diabetes by helping to control blood sugar levels. They highlight the goal of doing a minimum of 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity. This shared across the week is 20 to 25 minutes of activity everyday. This 20 minute workout can be any activity that gets you moving, such as walking, doing chores, keeping up with small children - anything!

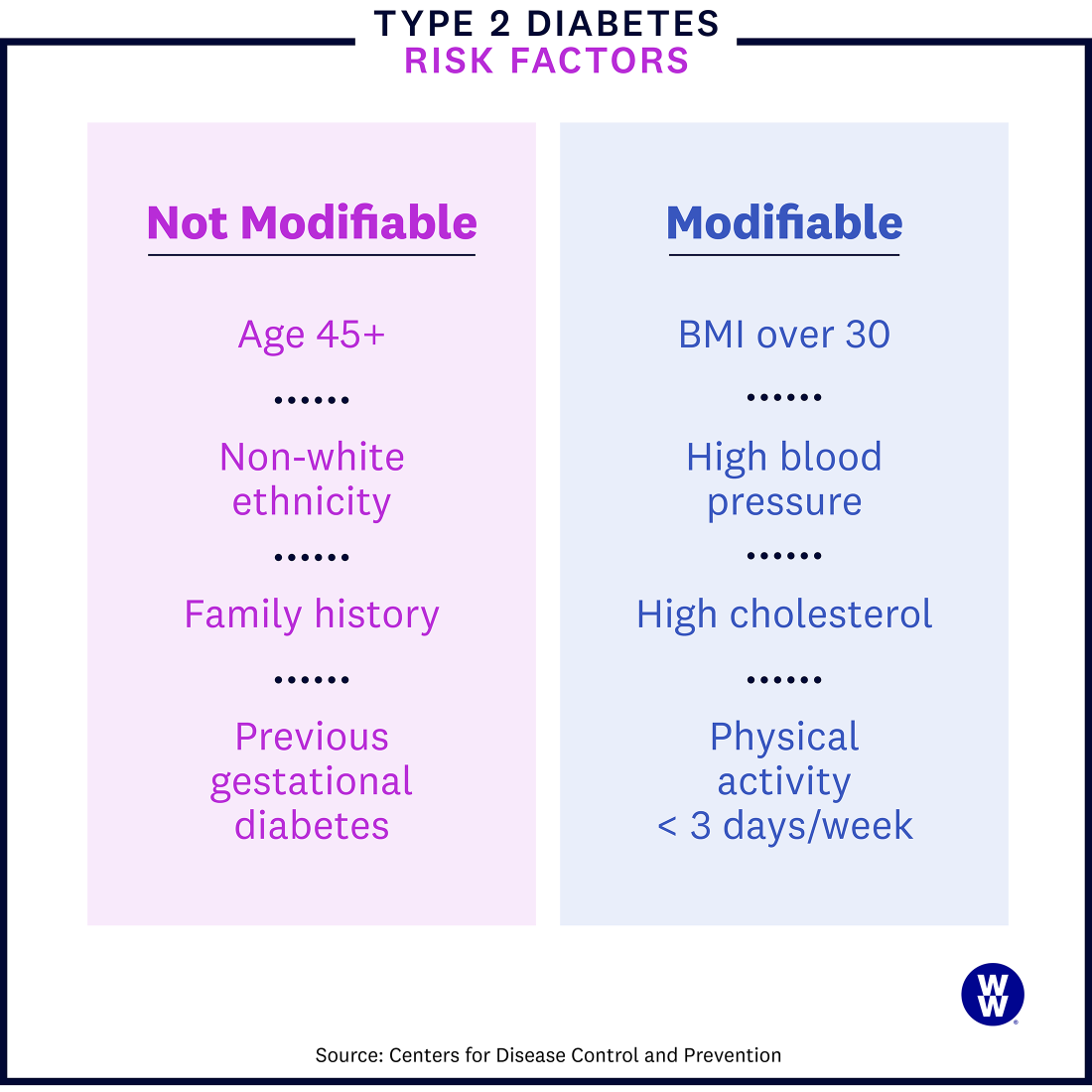

How do other health conditions impact your type 2 diabetes risk?

Suffering from high blood pressure (hypertension) and high cholesterol (especially in those who have high triglyceride levels) increases your chances of developing type 2 diabetes. “This combination of conditions is called metabolic syndrome; all the components of metabolic syndrome also put you at increased risks of heart disease and strokes,” Donner says.

That said, modest weight loss, eating healthier foods, and upping your exercise can lower the risk of all these conditions. Just 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity daily reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 58%.

- Blood pressure

Also known as hypertension, high blood pressure not only stresses the heart but also tends to co-occur in those with diabetes. Research shows the prevalence of hypertension is two times more likely in people with diabetes. Plus, those with hypertension are more likely to experience insulin resistance, and therefore diabetes as well.

- Cholesterol levels

Low levels of HDL cholesterol—sometimes called good cholesterol—and/or high levels of triglycerides can increase the risks of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease by directly impacting blood sugar levels.

How health disparities impact type 2 diabetes risk

Researchers have found that certain racial and ethnic groups and those in a low income bracket face powerful inequities when it comes to social determinants of health, which puts them at a greater risk of developing T2D. For example, according to Diabetes Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are almost four times more likely than non-Indigenous Australians to have diabetes or prediabetes. The same can be seen within the New Zealand population, with the prevalence of diabetes in Māori and Pacific populations being around three times higher than among other New Zealanders.

Tell me more about...

diabetes and inequities

diabetes and inequities

Q: Do those factors increase the risk of complications from diabetes too?

A: Unfortunately, yes. T2D tends to develop at an earlier age in many minority populations, and it’s often less controlled, which can lead to other issues. “Complications like kidney disease are more common in racial and ethnic minority patients with diabetes,” Donner says. Why? It’s harder to get the right care. Screenings for complications are performed less frequently, due to lower rates of healthcare coverage and also less support from the healthcare system.

Q: Can where you live affect your diabetes risk?

A: Our environment profoundly affects our health, and that applies to diabetes. If you live somewhere without access to safe recreational areas or to healthcare providers, as is the case in rural and urban communities alike, you’re more likely to develop health conditions like diabetes. Plus, says Donner, you will often be diagnosed with diabetes at a later stage. Meaning: You can develop diabetes complications even before you are diagnosed.

Is prediabetes caused by the same factors as type 2 diabetes?

Prediabetes basically means your blood sugar is higher than normal, but not high enough to merit a diabetes diagnosis. A fasting blood sugar level of 100 to 125 mg/dl (milligrams per deciliter) indicates you have prediabetes, while 126 and above indicate diabetes. Like type 2 diabetes, the specific cause of prediabetes is not well understood, but genetics, excess weight (especially around the belly), and lack of activity play a role. Risk factors are the same as with T2D: family history, race, age, living with excess weight or obesity, a lack of activity, and a history of other conditions like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease.

What causes gestational diabetes?

Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes that is unique to pregnancy, affecting nearly 10% of pregnant individuals. Researchers suspect it develops due to a mix of hormonal and genetic factors.

For starters, the placenta produces hormones like oestrogen and cortisol that can block the work of insulin—carrying sugar from the bloodstream to the cells—resulting in insulin resistance.

While pretty much everyone develops a degree of insulin resistance during pregnancy, the pancreas makes up for it in most cases by producing more insulin. When that’s not enough, though, the blood sugar levels rise and rise and gestational diabetes sets in.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, this tends to happen as the placenta grows and its hormone production scales, says Nicole Lynch, an advanced practice registered nurse at the Utah Diabetes & Endocrinology Center at the University of Utah, United States.

The good news is that “once the placenta is delivered, the person does not experience this resistance any longer and the diabetes goes away,” Lynch says.

It’s worth noting, however, that having gestational diabetes does increase your risk of T2D— nearly half the number of women with gestational diabetes go on to develop T2D later in life. (Though your risk of T2D increases with age regardless of gestational diabetes.)

What raises your risk of gestational diabetes?

In addition to hormones and genetics, there are some other factors that can make you more susceptible to the condition.

- Previous gestational diabetes. While gestational diabetes disappears after the baby is delivered, it does up your chances (significantly) of getting it again during future pregnancies. In fact, studies show you are nearly 50% more likely to get gestational diabetes again.

- Having a big baby. Previously giving birth to a baby weighing more than nine pounds (4 kilograms) increases the chances of developing gestational diabetes during future pregnancies. This is because delivering a larger baby—known as a macrosomic infant—is a sign of insulin resistance, Lynch says.

- Excess weight or obesity. Having excess weight or obesity prior to pregnancy can increase your risk of gestational diabetes. Studies show age heightens those risks. The older you are and the higher your pre-pregnancy BMI, the greater your chances of developing the condition.

- An age of 25 years or older. The older you are, the harder your pancreas has worked over time. So its ability to keep up with your insulin needs during pregnancy may be diminished.

- Family history of type 2 diabetes. If a parent or sibling has T2D, you’re automatically predisposed to diabetes, including gestational diabetes.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). According to the Medical Journal of Australia, as many as 8–13% of women of reproductive age are affected by PCOS, with around 21% of Indigenous women affected. PCOS is a condition in which the ovaries produce an abnormal amount of androgens, which can lead to insulin resistance. As many as 40% of those with PCOS are also insulin-resistant. This can spur elevated blood glucose levels that can lead to gestational diabetes, prediabetes, and T2D.

- Socioeconomic status. Lower-income individuals are more likely to live in under-resourced neighbourhoods. Within these communities, social determinants—such as poverty, lack of access to healthy food, restrictions on safe physical activity, inadequate employment, and limited educational opportunities—can result in a variety of negative health outcomes, including an increased chance of developing gestational diabetes and T2D.

- Race. People in marginalised racial and ethnic communities are more affected by gestational diabetes (as well as T2D). Research indicates that this is largely due to decreased access to health-related resources, increased stress, and lower socioeconomic status more likely to impact under-resourced communities.

This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It should not be regarded as a substitute for guidance from your healthcare provider.