What’s the difference between overweight and obesity?

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, overweight and obesity actually have very specific definitions, both based on the increasingly controversial classification system known as body mass index (BMI). And while being diagnosed with either can be a marker of your health, the diagnosis itself doesn’t tell you all that much. Here’s what you should know so you can take the best care of yourself.

What is overweight?

Affecting an estimated 36 per cent of adults in Australia and 34 per cent in New Zealand, overweight refers to an excess of body fat. It’s screened for using BMI, even though BMI doesn’t actually measure levels of fat; it measures your weight in comparison to your height. (You can find this number most easily with a BMI calculator).

In some cases a higher BMI isn’t linked to having overweight or obesity (an elite athlete will have a higher BMI due to extra muscle, for example), as the BMI screening tool was developed to evaluate risk at the population level, not the individual level. That said, BMI has the benefit of being easy to calculate, unlike other indicators of body fat, like dual x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans or underwater weighing.

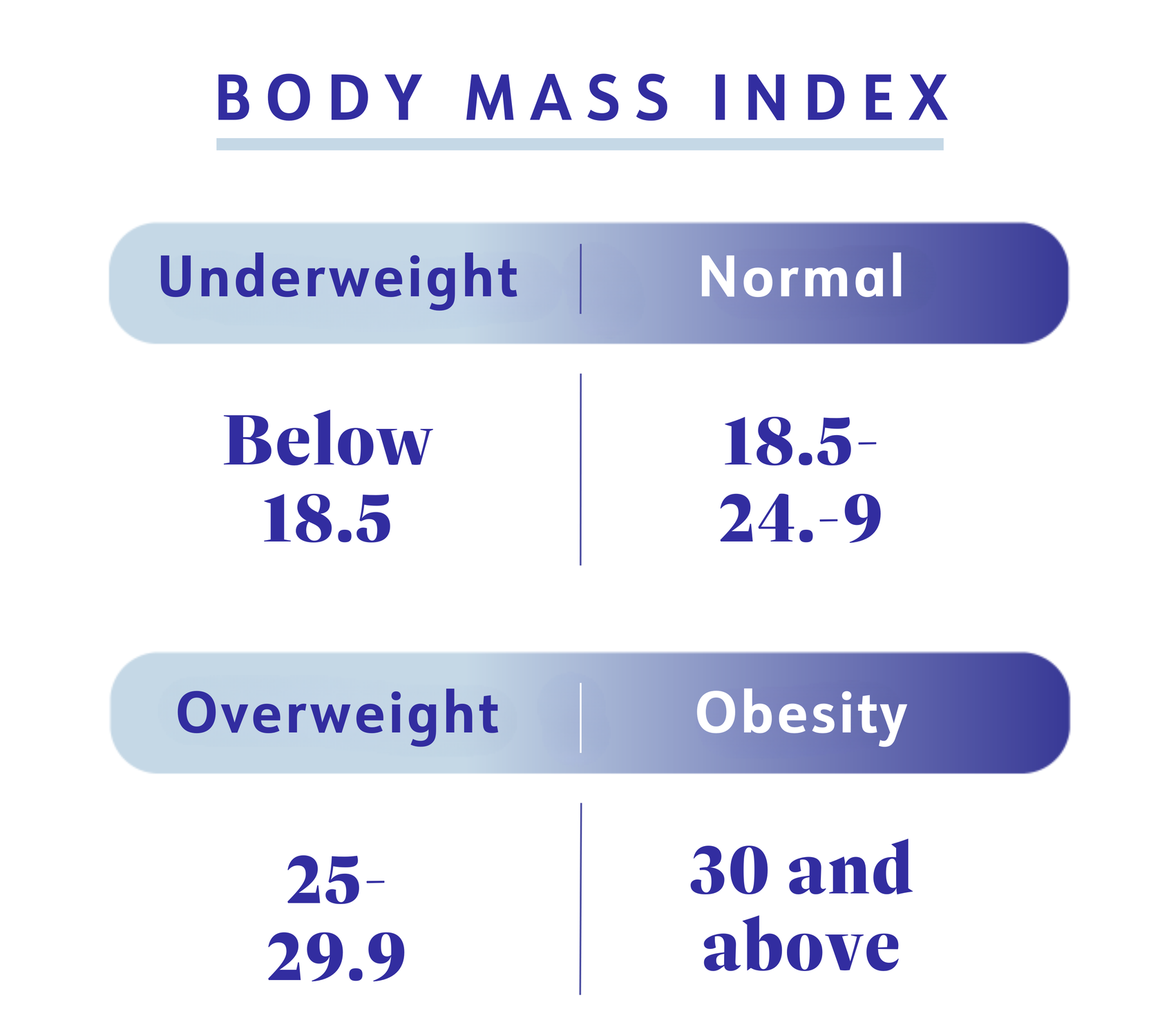

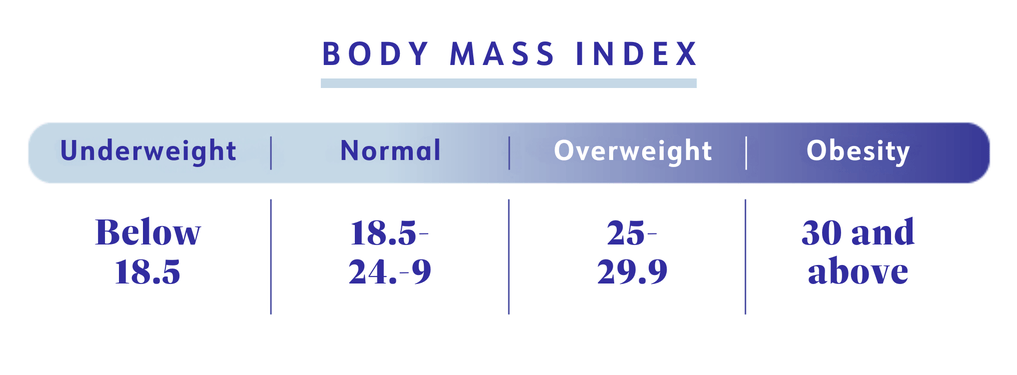

A BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is considered healthy, and a BMI of 25 to 29.9 is classified as overweight or pre-obesity. For the latter, that means a weight between 73 and 86 kilograms for someone who is 170cm.

What is obesity?

Just like overweight, obesity is an excess amount of body fat that’s most commonly determined by BMI. Once BMI reaches 30 or above, someone is considered to be in the obesity range—and this is the case for more than 31 per cent of adults in Australia and 34 per cent in New Zealand. Obesity is a progression of overweight and is recognised as a chronic disease by the World Health Organization (WHO). And this distinction matters, says Alexandra Lee, PhD, manager of clinical research at WeightWatchers.

“If something changes how our body normally functions—from tiny cells to large systems—then it’s classified as a disease, and obesity can lead to a number of abnormalities, like insulin resistance and infertility, for example,” says Lee.

"[Obesity] is an abnormal physiological process. We would never look at someone with asthma and tell them it’s their fault their lungs aren’t working."— Alexandra Lee, Ph.D.

Besides the fact it meets the medical criteria, calling obesity what it is—a disease—is important because it helps both patients and healthcare providers better advocate for adequate care. “This is an abnormal physiological process,” adds Lee. “We would never look at someone with asthma and tell them it’s their fault their lungs aren’t working.”

To help doctors determine health risks and appropriate treatment options, the World Health Organization classified obesity into three categories. The higher the class, the greater the chance for most individuals to experience obesity-related health complications:

- Class 1 obesity: BMI 30 to <35

- Class 2 obesity: BMI 35 to <40

- Class 3, or severe obesity: BMI of 40 or higher

The limits of BMI

There are a growing number of healthcare providers who are moving away from using BMI. “It can be helpful for estimating risk at the population level, but its usefulness is limited at the individual level,” says Lee. “It doesn’t account for the range of factors that impact someone’s health and weight status.”

So while there are health risks that are linked to having overweight or obesity, having a BMI that qualifies you for either category shouldn’t be some final verdict on your health. Rather, it should be the start of an in-depth conversation between you and your healthcare provider.

On the laundry list of things your BMI can’t tell you: whether your fat is concentrated in the abdominal area (where it’s most linked with obesity-related complications); if you go for a walk every morning; whether you’re getting solid overnight sleep; if your dad has high blood pressure and you inherited the genes for it too; and countless other factors.

Also, if the cut-off points feel slightly arbitrary, that’s because they are, acknowledges Steven B. Heymsfield, MD, an obesity specialist and professor at Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, LA, United States. Having a BMI of 25.1 compared to 25 doesn’t mean you all of a sudden are a lot unhealthier.

“The whole premise of defining someone like this is fraught with hazards, inaccuracies, and limitations that leads to a lot of confusion, stigma, and distress from people and healthcare providers,” says Robert F. Kushner, MD, professor of medicine in endocrinology and medical education at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, United States. That’s one reason why obesity researchers are currently developing diagnostic criteria that goes beyond BMI and looks at actual health markers, says Lee.

Overweight health risks

Overweight (pre-obesity) can have health risks, too. For example, a 2016 Danish study published in JAMA that looked at more than 100,000 adults concluded that the risk for mortality doesn’t start going up until BMI hits 27, which is firmly in the “overweight” category. Researchers believe this might be due to a smaller prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and improved treatments for conditions like high blood pressure.

Another 2022 study in JAMA Network Open looked at 30,000 adults around the age of 40 and found that a person with overweight was associated with a greater risk of developing heart disease as an older adult compared to those with a healthy BMI. The researchers also noted that those with overweight were more likely to live a greater proportion of their lives with disease. Further backing that up: A large-scale study has found that BMIs above the “healthy” range are associated with heart disease, heart failure, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

Obesity health risks

The scientific research is clear: There are many dangerous health conditions associated with obesity. The extra fat (adipose tissue) makes it harder for your body to regulate blood sugar, and raises inflammation throughout the body which can lead to serious health issues, including over 200 obesity associated disorders. And as BMI and body fat increases with the disease of obesity, the risks get higher. Here are just a few of the conditions linked to obesity:

- Certain types of cancer

- Depression and anxiety

- Fatty liver disease

- Gallstones and gallbladder disease

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Osteoarthritis

- Sleep apnea

- Stroke

- Type 2 diabetes

How overweight and obesity are treated

“If your [healthcare provider] diagnoses you with overweight or obesity, the next thing to do is find out what your health status is,” says Dr. Heymsfield. This means looking at things like your blood pressure, cholesterol numbers, and how much your weight impacts your daily life. They’ll likely explore possible contributing factors as well, including:

- Genetics

- Eating habits

- Stress

- Physical activity

- Medications

- Sleep

- Family history

- Social factors like food insecurity

- Other health conditions

If there are red flags that your weight is seriously impacting your health, your healthcare provider may recommend weight loss, which has been shown to make a big difference in even small amounts. If you’re living with pre-obesity or obesity, for example, losing just 5% of your body weight may be all you need to decrease the chance of prediabetes moving into diabetes.

If you and your healthcare provider have decided that treating obesity will help improve your health, you can talk about the right approach for you. There are currently three evidence-backed ways to go about doing that, says Dr. Kushner:

- Lifestyle changes: “This is what we call foundational. It’s how you eat, move, manage stress, maintain social connections, and sleep, as well as your relationship with alcohol and tobacco,” says Dr. Kushner. These behaviour-change strategies are core to weight loss programs like WeightWatchers, and for some people, they’re enough to lead to weight loss and better health.

- Prescription weight-management medications: Prescription medications impact the brain and hormones that are not functioning correctly from the disease of obesity. Prescription medications to treat obesity and assist with weight loss aren’t for people with a little overweight and no health risks. Your healthcare provider may prescribe them to you if your BMI is at least 30, regardless of whether or not you have any other health issues. They could also prescribe them if you have a BMI of 27 and qualifying health conditions like high blood pressure or type 2 diabetes. Medications aren’t a quick fix, just as a lifestyle change isn’t. For lasting change, they should always be combined with the healthy lifestyle habits listed above.

- Bariatric surgery: Weight-loss surgery impacts your digestive system, changing the hormones of weight regulation as well as, in some surgeries, decreasing the stomach size. Surgery is intended for people who have either severe obesity (BMI of 40 or higher) or obesity with qualifying health conditions, like type 2 diabetes. It also requires lifestyle changes to be successful.

The bottom line

The classification of overweight and obesity are often based on BMI numbers, something that should only be used as a starting point for a more in-depth conversation with your healthcare provider. Together you can determine if treating obesity with weight loss would benefit your health—and exactly how to get there safely. This discussion should centre around the treatment approach that’s most appropriate for you in terms of your health, lifestyle, resources, and goals.

This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It should not be regarded as a substitute for guidance from your healthcare provider.

Overweight and obesity definition: World Health Organization. (2021) “Obesity and overweight.” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

Overweight categorization: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022) “Defining Adult Overweight & Obesity.” https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.htm

Overweight statistics: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022) “Obesity and Overweight.” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

Obesity statistics: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022) “Adult Obesity Facts.” https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

BMI and mortality risk: Journal of the American Medical Association. (2016) “Changes in Body Mass Index Associated with Lowest Mortality in Denmark, 1976-2013.” https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2520627

BMI and heart disease risk: JAMA Network Open. (2022) “Association of Body Mass Index in Midlife With Morbidiy Burden in Older Adulthood and Longevity.” https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2790100

BMI and heart health: European Heart Journal. (2021) “Association between adiposity and cardiovascular outcomes: an umbrella review and meta-analysis of observational and Mendelian randomization studies.” https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/42/34/3388/6333298

Obesity health risks: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. “Obesity.” https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/research-areas/obesity

Obesity heart health risks: Circulation. (2021) “Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association.” https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000973

Additional health risks of obesity: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022) “Consequences of Obesity.” https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/consequences.html

Cause of obesity health risks: Johns Hopkins Medicine. “Overview of Obesity.” https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/obesity/overview-of-obesity

Weight loss and blood pressure: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2003) “Your Guide to Lowering Blood Pressure.” https://ghk.h-cdn.co/assets/cm/15/11/54ff77204744d_-_hbp_low.pdf

Weight loss medications: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. “Prescription Medications to Treat Overweight & Obesity.” (2021) https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/prescription-medications-treat-overweight-obesity

Weight loss surgery: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2020) “Definition & Facts of Weight-loss Surgery.” https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/bariatric-surgery/definition-facts

Weight loss medication and improved health conditions: Endotext. (2021) “Pharmacologic Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279038/

BMI benefits: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011) “Body Mass Index: Considerations for Practitioners.” https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/bmiforpactitioners.pdf